More Priuses Won’t Make Much Difference (Fewer Suburbans Will)

It is common to hear people say that we need more Americans to drive Priuses, hybrids, and other cars with good mileage. But measuring fuel efficiency by miles per gallon (MPG) is worse than useless: it’s misleading. It makes it almost impossible to easily compare cars and figure out how much fuel each car will really use.

We Should Focus on Minimizing the Fuel We Use, Rather than on Maximizing the Distance we Can Drive

We use MPG in the United States to measure a car’s efficiency. As you probably know, MPG measures how far a car can go on a given amount of fuel. This means that MPG is a good way to measure efficiency if you’re trying to maximize the miles you drive. MPG is not the best measure of efficiency, though, because most people drive a similar number of miles per week. According to the Federal Highway Administration’s National Household Travel Survey, the average miles driven per driver per day is consistently about 31 miles per day during the week (27 on Saturdays and 22 on Sundays).1 Demand for gasoline is inelastic: as gas prices change, the quantity purchased by drivers does not change very much. 2 I think that this is because people rely on their cars for transportation, and can only cut the distance they drive costs so much, since they still need to go to work, shop for groceries, etc. So, really it is not demand for gasoline that is inelastic, but demand for a given amount of transportation.

Because people will tend to drive the same amount, regardless of the cost of gasoline, then all other things being equal, most car buyers will still try to maximize their car’s efficiency. Thus, whether they like SUVs or compacts, if car buyers have two options that are identical in every respect except for different fuel efficiency, I think that most of them will choose the car with better fuel efficiency. Of course, different car models are never exactly identical, and fuel efficiency is just one of many factors a buyer will consider. MPG does not give car buyers the best information to make an informed choice. Since the miles we drive is usually pretty constant, what most of us should want to do is to minimize the amount of fuel we use to go a given distance, rather than maximize the miles we can go on a given amount of gasoline.

There are other good reasons for us to focus on decreasing fuel consumption, rather than maximizing the miles we drive. At the national level, many Americans would like our country to decrease its dependence on foreign oil. Assuming that domestic oil supplies stay constant, the only way to do that is to decrease the petroleum we consume, not to maximize the miles we drive. Similarly, most people would like to minimize the pollution created by automobiles. Since the number of miles driven is pretty constant, using less gasoline per mile driven is a great way to accomplish that.

MPG is Inadequate

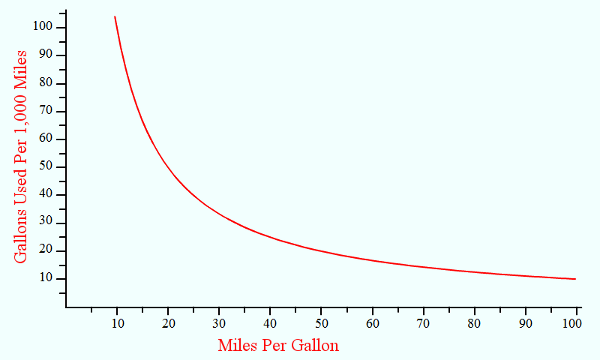

MPG isn’t the best way to help people understand the best ways to minimize fuel use. It is deceptive because it obscures the real differences in efficiency between cars. When people buy cars, they tend to think that the improvement in fuel consumption between a 10 MPG car and a 15 MPG car is the same as the improvement between a 15 MPG car and a 20 MPG car. This is not true. As MPG increases at a linear rate, the improvements in fuel efficiency decrease at a hyperbolic rate. This means that the greatest gains in fuel efficiency don’t come from building more cars with very high MPG, but by replacing the cars with very low MPG. To help new car buyers better grasp this, instead of using MPG, we should rate cars based on how many gallons it takes to go a given distance, such as Gallons per 1,000 Miles (GPM).

The following table helps illustrate why GPM is a better measure. The table gives us a comparison of a set of hypothetical cars. The first column shows the MPG of the car. The second column shows GPM, or in other words, the gallons of fuel it would take to drive 1,000 miles in that car. The next column shows the amount of gas saved by driving this car instead of driving the worst car (in our chart, a car with 10 MPG, which is the MPG for city driving of a 2011 Chevrolet Suburban3). The next column shows the incremental amount of fuel saved by driving this car instead of the car listed just above it in the chart. As you can see, the fuel savings from switching from a 10 MPG to a 15 MPG car is 33 gallons. The savings from going from a 20 MPG car to a 25 MPG car is 10 gallons. To save 10 gallons from a 50 MPG car, you’d have to switch to a 100 MPG car. There are rapidly diminishing returns for developing cars with ever-higher MPG.

This graph shows how quickly the fuel savings tapers off. The x-axis shows miles per gallon. The y-axis shows the gallons of gasoline used to travel 1,000 miles. As you can see, there is a steep drop off from 10 MPG up to about 25 MPG. After 25 MPG, the curve’s slope decreases significantly (meaning that you get less and less fuel savings from each improvement in MPG), and after 50 MPG, the curve flattens out considerably (meaning that the fuel savings become pretty minimal).

A Hypothetical Example

An example might help show how big a difference using GPM can make. There are about 250 million cars in the United States.4 Cars in the United States average about 17 MPG.5 To simplify things, let’s imagine a hypothetical world where all cars in the United States either get 30 MPG or 10 MPG. To get an average of 17 MPG, this would mean that there would be 87.5 million cars that get 30 MPG and 162.5 million cars that get 10 MPG. Assuming that people drive an average of 900 miles per month, in our hypothetical example the United States would be using 17.28 billion gallons of gasoline per month.

Now let’s assume that we want to increase the country’s average MPG to 20, but only by changing one of the two types of cars. If we did this by increasing the MPG of the 30 MPG cars, we would have to increase them to 38.5 MPG. After this change, the total fuel usage would be 16.67 billion gallons per month, which would save 584 million gallons of gasoline.

If we decided to increase the MPG of the 10 MPG cars (but leave the 30 MPG the same), we would have to increase them to 14.62 MPG. After this change, the total fuel usage would be 12.63 billion gallons per month, which would save 4.65 billion gallons of gasoline. The net change in average MPG would be the same, but increasing the efficiency of the 10 MPG saves almost 8 times more fuel than changing the 30 MPG cars.

Conclusion

So what does this all mean? Are programs like Cash for Clunkers a good idea, since they encourage people to replace low MPG with high MPG cars? No. There are considerations other than fuel efficiency to consider (such as the inefficiencies involved in destroying still-functioning cars and then manufacturing their replacements). Cash for Clunkers produced a net loss for the economy – for each car in the program, the total costs outweighed the benefits by $2,000.6 Accounting for all of the costs and benefits, the program thus lost $1.4 billion.7 A study by Edmunds indicated that the program cost $24,000 for each new car sale it generated.8 Additionally, because manufacturing a new car uses significant resources, replacing an already-existing functioning car with a new car causes waste that is difficult to offset, even considering the newer car’s greater fuel efficiency.9

The best thing we can do is make information about GPM easily available to car buyers, so that they can make better-informed decisions when they’re buying a car. It is easy to calculate – all you do is take the reciprocal of the car’s MPG (divide the MPG by 1), and then multiple it by 1,000:

The U.S government requires car manufacturers to list MPG for city and highway driving on cars. It would make a lot more sense to require that they list GPM.

Until it becomes standard to list GPM information for each car, though, you can at least calculate it out yourself and become a more informed car buyer.

Footnotes

1 http://nhts.ornl.gov/tables09/ae/work/Job13285.html. Here is the data for each day’s average miles driven:

One thought on “More Priuses Won’t Make Much Difference (Fewer Suburbans Will)”

Have you seen this new type of engine? They claim 4x more efficient than gasoline combustion engines: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/42460541/ns/technology_and_science-innovation/

Also I know the math might get a little mushier but could you include manufacturing, repair, maintenence costs for little cars and hybrids vs. SUVs and SUV hybrids? Maybe just a couple of examples since there are too many products to run them all…